JUNGLE HAMMOCKS

Che Guevara ranked a hammock number one among the most essential items of personal equipment needed by a jungle guerrilla. In his authoritative book, Guerrilla Warfare, he described the political strategies and the weapons, personal equipment, and tactics needed to create and win communist revolutionary wars. His 1960 book should have alerted America’s leaders to what was in store for our soldiers and other anti-communist troops from Vietnam to El Salvador.

Regarding a jungle fighter’s personal equipment, Che Guevara began by stating:

The ease with which the guerrilla carries out his tasks and adjusts to his environment depends upon his equipment. For us in Cuba, essential gear included hammock, nylon rain cloth, blanket, jacket, pants, shirt, shoes, canvas back-pack, and food such as butter or oil, canned goods, preserved fish, condensed or powdered milk, sugar, and salt. The hammock was the key to a good night’s sleep.

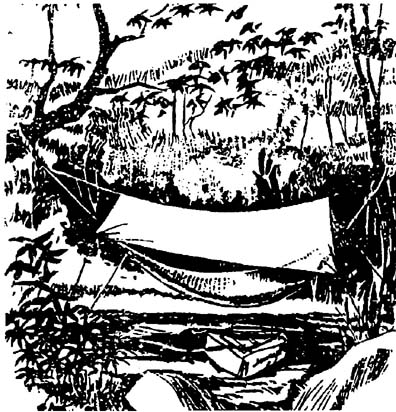

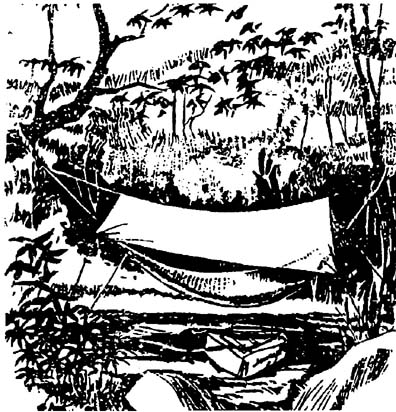

The above quotation is from a somewhat abbreviated translation of Guerrilla Warfare made by Major Harries-Clichy Peterson, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve. His translation was first published in 1961 by Frederick A. Praeger and is the one most read by Americans. Major Peterson significantly omitted Guevara’s only illustration of an item of personal equipment, a drawing of a jungle hammock complete with separate rain canopy. (See Fig. 15-1.) That drawing is in a widely circulated Spanish edition. I bought a copy in a communist book store in Mexico City in 1961 and found it fascinating reading. Perhaps Major Peterson omitted the hammock illustration because Marines have not had jungle hammocks since shortly after the end of World War II. A copy of that drawing or a similar one appeared in an English translation, published in MR Press in 1961, of Che Guevara’s important book. Che Guevara advised the guerrilla to have a mosquito net, but did not list one as essential equipment.

Fig. 15-1. Hammock with a separate lightweight rain canopy (“a nylon roof”), described by Che Guevara as parts of a Cuban guerrilla’s essential equipment. Note that the corners of the rectangular rain canopy are tied with strings to shrubs to form a gabled roof. No mosquito netting is shown; Cuba’s wooded mountains are not pestilential jungle.

Hammocks are more important to foot-mobile fighters in jungles of the Americas than in the humid tropics of Asia. Biting, stinging, crawling pests in Central and South American jungles forced the natives to become a hammock people, with millions being conceived, growing up, multiplying, and dying in hammocks. Since it is generally agreed that American foot soldiers and friendly troops are more likely to fight in Western Hemisphere jungles than in Asian ones, our Army should make and jungle test Jungle Hammocks with their attached sandfly netting sides and attached rainproof canopies, and open hammocks. The open hammocks should be similar to the Model 1966 jungle hammocks issued until early in the 1990s, but with false bottoms added, as described later in this chapter. Both types should be updated, mainly by using today’s lighter, stronger materials.

In 1996 most Army officers knew very little about hammocks of the kinds that had been used by jungle fighters. An account of such hammocks follows, summarizing their development, uses, and limitations.

BACKGROUND OF THE U.S. ARMY’S WORLD WAR II

JUNGLE HAMMOCK

Before World War II, American soldiers were issued no hammocks. Our Marines did not use theirs when ashore. In contrast, American exploration geologists for decades before Pearl Harbor had found that hammocks, sandfly nets, and rain canopies were essential to their work in Central and South American jungles.

Before joining a Standard Oil of Venezuela exploration party in 1940 in a very sparsely inhabited jungle region in the Orinoco Basin south of the Venezuelan Andes, I was issued complete hammock equipment sold to Standard Oil and others by the Fiala Company, an explorers’ outfitter. The sleeping equipment consisted of a handmade, knotless-bed string hammock of the best South American type, a box-like, suspendable, zipper-closed sandfly net with a waterproof cloth floor and conical netting sections at its two ends to fit over the hammock’s bridle cords, and a lightweight waterproof cloth canopy to be suspended separately from the same two trees. All three items together weighed about 10 pounds, a small concern to peacetime geologists who had native porters to carry their sleeping gear, food, guns, and heavier instruments when working for days away from their mule-mobile base camps.

My first night sleeping in a hammock in jungle ended with excruciating, prolonged pain. To keep from bringing chiggers or ticks with me into the zipper-closed sandfly netting, I hung my sweaty clothes outside on the hammock ropes and left my shoes and socks on the bare ground. On awakening at dawn I first put on my clothes. Then before putting on a shoe I began shaking out the sock. Out fell the biggest scorpion I had ever seen, about four inches long when its stinger was extended. A whack with my shoe ended that danger. Congratulating myself on knowing how to take care of myself in jungles, I was starting to pull on the sock when a searing pain struck my left thumb. A second large scorpion was inside my sock; its stinger had pierced the end of my thumb! My yell of extreme pain brought most of the exploration party to me. A geologist put a tourniquet on my wrist; all advised me to lie still in my hammock throughout the morning. The lymph glands in my armpit swelled. Aspirin did not stop the surges of pain.

The camp cook, a middle-aged Trinidadian black, was my only company all that day. When bringing me water and aspirin he tested my mettle by describing in detail how several children had died in Trinidad from the stings of scorpions not as big as the one that had stung me. He told me that I should have hung my socks and shoes off the ground, with the shoes suspended by their laces after having treated the laces with insect repellent.

By noon I stopped using the tourniquet. By nightfall the pain was dull. Convinced that jungle explorers and jungle soldiers should receive excellent sleeping equipment accompanied by detailed written instructions on how to avoid jungle hazards, I ate dinner with the two American geologists. They had returned from their day’s mapping of outcrops along the river beside which we were camped.

In jungle lowlands I usually slept naked in the steamy heat, sometimes awakening to hear drops of sweat hitting the rubberized cloth floor of my sandfly net, after running from my body through the sweat-wetted part of my string hammock. In cool foothills of the Andes I wore dry clothes and a light sweater when sleeping in my airy hammock.

While working in Venezuelan jungles I became increasingly concerned about my unprepared country’s approaching war to stop Hitler’s and Japan’s extending conquests. As a reserve officer, a first lieutenant of infantry, I believed that American soldiers probably soon would be fighting in jungles, and would need special equipment. So I began thinking about how to make an assemblage of equipment better and lighter than that provided by Standard Oil for its geologists exploring jungles.

For an improved hammock, one requirement would be a mosquito net, or rather a sandfly net to keep out much smaller insects than an ordinary mosquito net can stop. The net should surround the hammock but not touch the ground. That design requirement was brought home to me one unforgettable dark night in an Orinocan jungle. On being awakened by one of my two porters yelling “Huachacas! Huachacas!”, I grabbed my flashlight, turned it on preparatory to un-zipping my sandfly net and picking up my shotgun — and found that large parts of my net had disappeared! Huachacas, I later was informed, are vegetarian ants. Many thousands had invaded my three-man overnight bivouac and were busy cutting out hundreds of small pieces of my cotton sandfly net and carrying them away to their underground chambers. Those mushroom-raising ants, even more destructive of cotton fabrics than tropical cockroaches, also had cut holes in my two porters’ insect nets and in some of their clothing hanging on limbs. I had learned to hang my shoes and clothes from limbs, with a little “612” insect repellent on suspending shoelaces and strings, and to put repellent on a few inches of the hammock ropes close to where they went inside the sandfly net.

Huachacas are not stinging ants; they only bite. South American army ants, which kill most insects and many lizards, snakes, and even small mammals that can’t get out of their way in time, both bite and sting with deadly effect. Many other species of tropical ants both bite and sting. Along with scorpions, spiders, leeches, ticks, snakes, and other crawling harmful pests, ants make sleeping on the ground very undesirable even if using excellent insecticides/repellants.

The three of us cursed as we brushed off huachacas while breaking camp and moving to a gravel bar in the adjacent river bed. There we got a little restless sleep, protecting ourselves from mosquitoes as best we could by using our clothing, pieces of sandfly netting, and “612” insect repellent. Next day we returned to our mule-mobile base camp, where we were supplied with replacement sandfly nets.

One of the most dramatic dangers in hot parts of South and Central America is being bitten by a rabies-infected vampire bat. There many hundreds of domestic animals are killed each year by rabies contracted from bat bites. On one moonlit night I saw vampire bats silently hovering close to the sandfly net around my hammock, which was hung between two trees at the edge of a llano, a treeless open grassland. I was sleeping at our mobile base camp, and had been awakened by the tethered mules whinnying, stamping their hooves, and lashing their tails. Vampire bats were using their protruding, lancet-like teeth to make bleeding cuts in the mules’ withers, the highest parts of their backs, which they could not reach with their swishing tails. The anesthetic in the bats’ saliva prevented pain, but the mules smelled their own freely flowing blood and were alarmed. I recall my quiet satisfaction while watching a vampire bat in the moonlight fluttering inches away from my face, frustrated by my sandfly net. At dawn we noted the mules’ bloody withers.

Vampire bats caused Major General John K. Singlaub to appreciate more fully the need for mosquito nets in many Western Hemisphere jungles. As recounted in his wide ranging book Hazardous Duty, after his retirement from the Army he helped anti-communist fighters in Nicaragua obtain better weapons and equipment. One night a local Miskito Indian commander gave him the only mosquito net in the sleeping hut they occupied. When the Indian “rolled out of his hammock at dawn, his feet were streaming blood. Vampire bats had visited in the night; their saliva contained a natural anesthetic and anti-coagulant.”

Singlaub wrote: “I made a note to add mosquito nets to the supplies the MISURA [a coalition of anti-Sandinista Indian tribes] needed.”

Snakes are a minor actual hazard to a sleeping man, but a psychological problem to many Americans when sleeping on the jungle floor. Walking into a snake can be hazardous. One of my porters, moving about 10 feet ahead of me on a narrow trail, suddenly let out a yell and leaped ahead, with a four-foot fer-de-lance hung by its fangs on a trouser leg. His leap made the deadly snake fall off. He laughed, cut a stick with his machete, and killed the retreating reptile.